Cheyenne Mountain Joins the Ranks and Finally Breaks Tradition

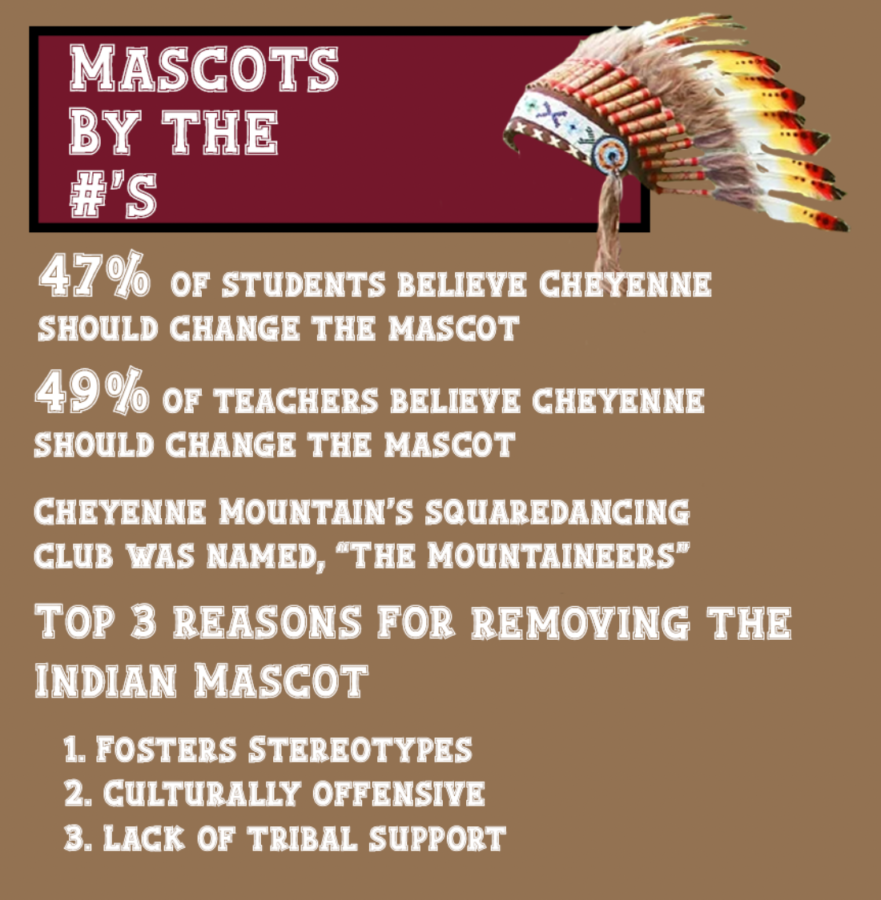

16 Colorado high schools have retired their Indian mascots. Recently voted on, the Indians have been retired from their decades-long reign beginning in the 60s.

Under pristine beige walls and manicured landscaping lies suburbian teenagers recklessly beating hide drums in flashy black-tipped headdresses, red war paint streaked across the loud cheeks of white students, and obnoxious chants bellowing from bare bellies.

Holding onto these distasteful values for the sake of a mascot depicted as wild or aggressive is not only passé, but culturally callous.

Today, these ideals blur the distinction between authentic school pride and fostering misconceptions about race.

The problem seems to be that these mascots were born during a time of accepted racism and bigotry. While it may be true that earlier generations played cowboys and Indians in their backyards at a young age, it doesn’t excuse the discrimination and merely dignifies the problem as we understand it today.

Embraced by a culture decades ago, labeling products, sports teams, and businesses with blatantly offensive names like Savages, Indians, and Redskins was considered dignifying and honorable. But when do we finally let go of the past?

“A common belief in the contemporary United States, often unspoken and unconscious, implies that everyone has a right to use Indians as they see fit; everyone owns them. Indianness is a national heritage; it is a fount for commercial enterprise; it is a costume one can put on for a party, a youth activity, or a sporting event,” writes Arlene Hirschfelder, historian and author of American Indian Stereotypes in the World of Children.

While Cheyenne may be proud to honor Native Americans via the Indians mascot and the incorporation of Akichita rituals, the naming of the Kiva, and its many blessings from local Natives, it’s time to end the era of tomahawk chops, misrepresentation, and ignoble stereotypes.

Schools, sports teams, and organizations are re-evaluating their names, stripping away the bits of evidence that bear labels of Native American culture, from the arrow to the dreamcatcher.

Sixteen high schools in the state of Colorado and 1,232 high schools total across the US carry American Indian mascots or school names. Amends on naming hadn’t begun until voices spoke out, ranging from the full subtraction to the greater emphasizing of the current mascot.

Representatives of indigenous associations have brought their voices to the light, advocating for the complete removal of the mascot. A Native-based and Native-led organization, located in North Dakota on the Northern Plains, home to the tribes of the Sioux, the Nueta, the Sahnish, the Hidatsa, and the Chippewa, have written to the Cheyenne Mountain School District 12 endorsing the replacement of the mascot, the Indians.

In the letter to CMSD, Cheryl Ann Kary, executive director of Sacred Pipe Resource Center, aimed at sourcing resources for indigenous people, stated, “We understand that our People are viewed as strong fighters and warriors. However, good intentions do not mean that characterizing our People as mascots is not hurtful and harmful.”‘

Unintended consequences, negative imagery, and cheap representation line the debate, with participants requesting educational incorporation of local culture. By the naming of buildings, activities, and varied material after sanctities, calls to not only remove, but reform, have surfaced.

A secretary and proud Chumash and Opata woman for District 12, Kailyn Enriquez said, “I truly believe that we are removing the history of all Native Americans from our past and current narratives all for political gains. I would hate to see the Traditions that our ancestors have taught and passed down to us for many generations just disappear. I think we should keep the mascot but add tribal traditions to the school.”

Similar to Enriquez, in a survey conducted by The Mountain News, multiple staff members of Cheyenne Mountain have suggested land acknowledgements, open communication with tribal leaders within the area, and even Wish Trees, a sacred prayer tree designated for granting wishes and offerings.

Encouraging multiculturalism and active participation modernizes our perceptions of Native Americans cemented to the pages of a history textbook.

Allegations consisting of the direct association between naming and ancient characterization describe the improper use of these titles composing Native American people as historical figures rather than contemporary members of society.

A 2015 study by researchers at Pennsylvania State University found that 87 percent of content taught about Native Americans includes only pre-1900 context, saturating the culture and its people with aged photographs and stereotypical “Indian” stories, painting a stagnant picture that isn’t representative of Native Americans on a modern level.

“This is a human rights issue, we are being denied the most basic respect. As long as our people are perceived as cartoon characters or static beings locked in the past, our socio-economic problems will never be seriously addressed,” said Native American Seminole Michael S. Haney.

Native Americans have the lowest rates of socio-economic indicators. Twenty-five percent of Native Americans live below the poverty rate, 6.6 percent are unemployed, and they have the lowest educational attainment rate compared to any other group. These rates are more than double of the general population.

To top the decades of overlooked hardship and inadequate respect, prejudiced hate crimes are precariously high against Native Americans.

“American Indians are more likely than people of other races to experience violence at the hands of someone of a different race. The rate of violent crime estimated from self reported victimizations for American Indians is well above that of other U.S. racial or ethnic groups and is more than twice the national average,” said Steven W. Perry, a BJS statistician with the U.S. Department of Justice.

As of February this year, Bill sponsor and Wheat Ridge Democrat Senator Jessie Danielson proposes to ban American Indian mascots in public schools, facing a monthly fine of $25,000 if not removed by June 1, 2022.

Are we really embracing Native American history and culture when it has a lofty price tag, metaphorically and literally?

How can it be tradition, multiculturalism, or diversity when the repeated imagery cannot be divorced from its original intent?